|

|

|

EPA/Facundo Arrizabalaga |

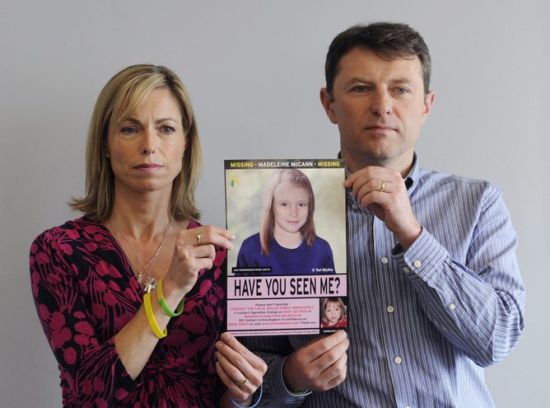

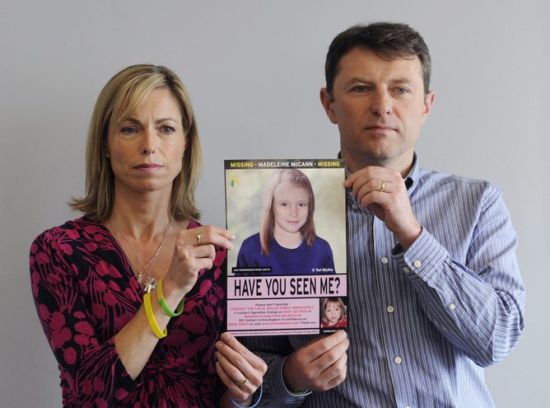

It is nearly seven years since a little

blonde-haired British girl named

Madeleine McCann disappeared from her

bedroom in a holiday resort in Portugal.

Madeleine, if she is alive, would be ten

years old now, having spent the majority

of her decade on earth separated from

her family, parents Gerry and Kate

McCann, and twin siblings Sean and

Amelia.

What happened that night in the Algarve

fishing village of Praia de Luz remains

a mystery. Was Madeleine abducted while

she slept, by a person or persons

unknown, as her parents claim? Or, as

the former head of the Portuguese

investigating team alleges, did she die

in apartment 5A of the Ocean Club

complex, her body disposed of in an

attempt to cover up negligence or worse?

Ongoing investigations by police teams

in the United Kingdom and Portugal have

failed to answer those questions, or to

find evidence sufficiently compelling as

to justify prosecutions in either

country.

The case continues to be a focus of

public, police and political attention

as the seventh anniversary of

Madeleine’s disappearance approaches,

and the trial of that same former

investigator accused of libel by the

McCanns comes to its conclusion in

Lisbon on Tuesday. Ex-inspector Goncalo

Amaral’s book, The Truth Of The Lie,

based on police work before the case was

‘archived’ due to lack of evidence,

advances the theory of Madeleine’s death

– accidental or intentional - and

hypothesises a staged abduction by the

parents.

For this he is being sued for over one

million euros in damages by the McCanns,

who allege that his book derailed the

search for their daughter when it was

published in 2009. The closing

statements and judge’s verdict on the

case are due this week in Lisbon.

My interest in this sad story is both

personal and professional. In the

northern summer of 2005 I took my

holidays at the Ocean Club, staying in

the apartment directly above 5A where

the McCanns resided in May 2007. A

friend of my parents owned the

apartment, and my extended family rented

it and two other units in the complex

for two weeks in July that year: my

parents in one, my sister and her family

in another, myself, my wife and my

brother in the apartment above 5a.

|

|

|

The beach at Praia. Brian

McNair |

Two weeks is enough time to get to know

the Ocean Club resort, and the

surrounding village of Praia de Luz,

quite well. I ate in the Tapas

restaurant, drank in Kelly’s bar, went

inside the beautiful church at the

village centre; I walked on the beach,

and the streets leading to it from the

Ocean Club. So when the news of

Madeleine McCann’s disappearance broke

on May 4 2007 it resonated and captured

my attention like no other crime story I

can remember.

Millions of people all over the world

were similarly captivated, but my sense

of proximity to the events gave me a

specially good reason to follow the

case. The fact that Gerry McCann was

Glaswegian like me was another point of

connection.

From my professional perspective as a

media sociologist, the disappearance of

Madeleine McCann was an early example of

the dramatic impact of the rise of the

internet and 24-hour news channels on

how human tragedies of this kind are

reported and understood by the public.

The mediatisation of ‘Maddie’, as she

became known to many, was unprecedented.

It involved professional public

relations practitioners, including

former senior UK government specialists,

in highly organized media management, or

‘crisis communication’, as one of the

agencies involved characterised its

services.

It engaged the British public in

discussion like no previous case, not

because the crime was unique (though it

was rare – the most recent case of

suspected abduction by a stranger of a

British child while on holiday overseas

had been that of Ben Needham in 1991),

but because the emergence of social

media – Twitter launched in 2007,

Facebook in 2004 - provided a new and

powerful platform for public sharing of

information, opinion and argument about

an ongoing criminal investigation.

From early in the investigation the

McCanns proactively used the internet to

issue appeals and information about

Madeleine to a global online public, as

did the police. Scotland yard’s

Operation Grange, set up to investigate

the crime in 2011, had its own hashtag

and website.

The public used the internet to access,

assess and discuss information about the

case as it emerged, and to speculate on

what had happened to the little girl.

Their sources included a mass of

official material produced by the police

in both Portugal and the UK, digitized

and made available online.

|

|

|

The church at Praia.

Brian McNair |

There were thousands of pages of

transcripts of interviews and court

testimony, detailed forensic

reports, summaries of findings by

investigating officers, court

rulings such as that by the

Portuguese Attorney General which

formally ‘archived’ the Madeleine

McCann investigation in 2009, all

neatly categorized and searchable on

sites such as

www.mccannpjfiles.co.uk .

Never before in the history of the

volatile relationship between crime,

media and public had so many people

had such easy access to so much

primary official data relating to an

unsolved, still active case.

By 2007 virtually all of the news

media were online, operating around

the clock with story updates, live

feeds and real time coverage of

events, commentary threads and links

to research materials. The unfolding

narrative of Madeleine McCann was

covered as it was happening, which

meant with glacial slowness,

punctuated by bursts of police

activity in the UK or Portugal.

Seven years on, that remains the

case.

There have been peaks and troughs in

the level of media and public

interest, corresponding to

newsworthy developments such as the

establishment of Operation Grange

and the BBC Crimewatch

‘reconstruction’ of October 2013.

The Lisbon libel trial of Goncalo

Amaral has been such a catalyst, and

its conclusion this week will drive

the disappearance of Madeleine

McCann back up the UK and Portuguese

media and public agendas.

The tone and content of the

coverage, and the public’s response

to it on social media, will be

determined in large part by the

Portuguese judge’s verdict. If

Amaral is found guilty, the McCanns

account of what happened to their

daughter will continue to set the

news agenda. If it goes the other

way, and Amaral is found not guilty

of defaming the McCanns in his book,

we can expect the world’s media to

report his hypothesis and the

supporting evidence more thoroughly

than has been the case up until now.

|