|

|

Parent's worst nightmare ...20,000 children

are reported lost in Australia each year.

Photo: Thinkstock |

Today is International Missing Children's Day. With more

than 20,000 children reported lost in Australia each

year, Claire Low explores one of the worst nightmares

that parents can face.

Isra Aksema's struggles are nothing short of dreadful: Missing

since August 2004 in the Netherlands, Isra was abducted

by her father after he killed her mother. She is 10

years old now and her picture reveals a pretty-in-pink

little poppet, smiling shyly at someone off-camera.

This is one of the many case studies on the International Centre

for Missing and Exploited Children's website.

This website isn't cheery. It also features the now-famous image of

strikingly pretty child Madeleine McCann, as she was at

the time of her disappearance in 2007 in Portugal, along

with an image of how she could look now, aged nine,

complete with distinctive right pupil running into the

blue-green iris.

|

|

Rebecca Kotz, team leader of the AFP's

National Missing Persons Coordination

Centre. Photo: Rohan Thomson |

Closer to home, there are the cases of Amelia Toa Hausia, born in

July, 1974, who has been missing since December 1992.

Last seen in a Canberra shopping centre, she vanished after a fight

with her boyfriend and has not been seen or heard from

since 1993 when she contacted her mother in Tonga to say

she was OK.

There is also Elizabeth Herfort, last seen in June, 1980, at the

Australian National University Union Bar in Canberra,

thought to have disappeared after hitchhiking. Another

person who vanished when she was younger, Megan Louise

Mulquiney, would be 44 now and hasn't been seen since

July 1984, after finishing work at Woolworths Woden,

just after noon.

|

|

Kate McCann stands in front of a picture of

her daughter, Madeleine, who went missing

during a family holiday to Portugal in 2007.

Photo: Reuters |

The collection of sad stories and pictures of children frozen in

time is linked to from the Help Bring Them Home website,

which promotes the cause of missing children for

International Missing Children's Day, which is today.

This website takes the form of a hauntingly empty

playground populated only by white balloons. Each

balloon, when clicked on, reveals another vanished

child: curly-haired Jasmine Sbaragli, missing since

January 1, 2009, from Lucca, Italy; grinning Rista

Chanthavixay, missing since March 2009 in NSW;

mop-topped Adrian Stoica Dumitru, lost since February 2,

2007, from Sintesti, Romania; and round-cheeked Abby

Maryk, missing since August 30, 2008, from Winnipeg,

Manitoba, Canada. Sad-eyed Fazli Saeem has been lost

since July 14, 2009, from Athens, Greece. Cameron

Leishman of NSW, missing since September 2008, squints

awkwardly into bright light.

Lost boys and girls are plentiful enough: of the 35,000 people

reported missing in Australia every year, about 20,000

of those are younger than 18. The good news, though, is

the vast majority aren't gone forever: ''In 99.5 per

cent of cases, they [police] find the child,'' Rebecca

Kotz says.

Kotz is team leader at the Australian Federal Police National

Missing Persons Coordination Centre. She is kind and

maternal - in fact, a mother of two herself. Her

darlings are an 11-year-old daughter and a 15-year-old

son.

|

|

The Beaumont children, who disappeared from

Adelaide in 1966. |

As part of her role at the centre, Kotz meets with Australian

families who are missing a loved one.

''I think they're incredible people,'' she says. ''If any of my

kids went missing, I would be a basket case.

''I don't know how some of [the families] survive, I really don't.

|

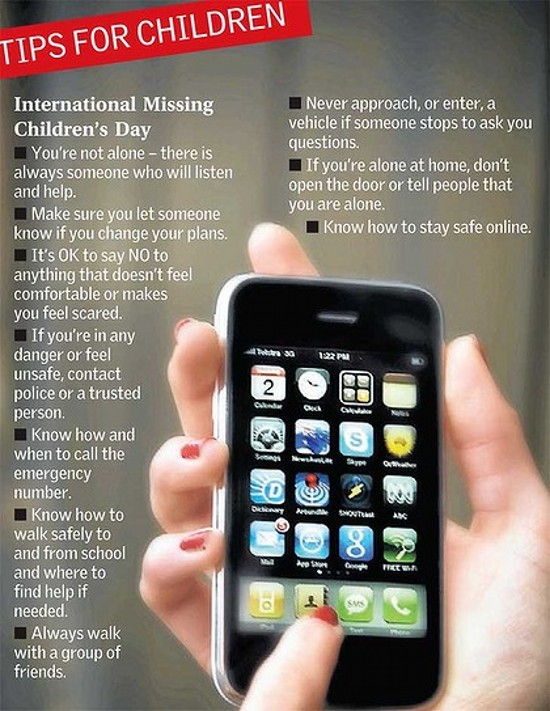

|

Tips for children to stay safe. |

''I can tell you, if it happened to me, I don't know how I would

carry on. I don't know how I would wake up and breathe

the next day. It would be horrific.''

Explaining what parents should do if faced with the predicament of

a missing child, she says there's absolutely no need to

wait.

One myth in Australia is that one should wait 24 hours to report

anyone missing.

''It's probably the worst myth,'' Kotz says. ''You don't have to

wait any time. If you have fears for the safety of a

loved one, you go straight to police and report them

missing.''

In fact, earlier is better.

''As soon as the trail goes cold, it's harder to trace somebody,''

Kotz says.

Another good thing - in Australia, children usually go missing for

an innocent enough reason: a failure to tell their

parents of a change of plans, according to Kotz.

Parental abduction figures in Australia are low with the

family court dealing with about 140 cases per year.

Stranger abductions are rarer still.

''We live on a massive island,'' Kotz says. ''There's not a long

way to take them unless you're a parent and you've got a

passport in your hand. It's very rare to find a Daniel

Morcombe case.''

Daniel was a Sunshine Coast teenager who went missing in 2003. His

remains were found, and a Perth man taken into custody

and charged with his murder, last year. His family set

up a foundation in his name to teach personal safety to

the young and vulnerable.

But, again, the chances of a case like this occurring are slim. In

her time at the centre, the number of stranger abduction

cases Kotz has dealt with she could count on one hand.

''We're lucky in Australia. Our main area of concern is … a child

in care who is a regular runaway,'' Kotz says,

explaining that a lot of the runaways in question are in

care services or foster homes, struggling with life and

rebelling. The child tends to simply be out with friends

rather than wherever they are supposed to be waiting to

be picked up.

Police searching for missing children take each report seriously.

They take as much information from the parents as

possible, then chase the child's friends, schools,

sporting associations, and anyone the child could be

connected with.

''All their procedures are very thorough,'' Kotz says. ''They don't

stop until they find the child.''

The child is not thought to be dead until a body is found. A

coroner can make a ruling, usually after at least seven

years, on evidence of life, not whether the child is

alive or dead. As long as the child is missing, the case

remains open. Here, Kotz cites the case of the Beaumont

children, who famously went missing in the 1960s. New

work had been done on parts of the investigation as

recently as last year.

''That case will not go away because it's an absolute mystery as to

whether those kids are now adults, not realising who

they were,'' she says.

At this point, Kotz becomes impassioned.

''Can I say one thing: the worst thing any media can do - and it's

really hard for families to deal with - is put the word

''closure'' to anything.

''Whether they find a body, whether they find the child alive and

well, whatever the case may be, it's never closure. Let

me make that perfectly clear.''

For the families, locating a child or a body only opens up more

questions. For instance, according to Kotz, a girl,

missing for two decades, was found fine and well, but

because of her personal issues, was unable to face her

family's questions once reunited with them.

''That is a success story, but it's still not closure,'' she says.

Mentioning Daniel Morcombe again, the locating of the boy's remains

and having something to bury likewise was not closure

for his family, who had ''been through living hell''.

''It opens up to [questions like] what did he go through in his

last moments and what happened to him?

''They have to live with that for the rest of their life.

''The one thing families say to me time and time again is people

saying, in the media, that they've finally got closure,

is the worst thing.''

It's almost impossible to imagine the profound pain families of

missing children must feel. Kotz describes her own heart

palpitations and immense emotions when her daughter,

then aged two, went missing. The girl turned up quickly

on a queen-sized bed at David Jones among a bunch of

teddy bears.

But for those stuck in limbo, not knowing, fearing the worst, what

must it be like?

Psychologist David Gorovic, of Canberra Counselling Services, says,

''The key experience is they are in limbo. To experience

grief, you need a definite loss. In this situation,

there is nothing definite.

''It's distressing and devastating because the brain doesn't like

uncertainty, doesn't like gaps. It fills gaps with

imagination: [parents] imagine all sorts of horrible

things. People imagine the worst and imagination becomes

reality. Then they react to what they imagine, not to

what happened.''

He finds the known can be easier to deal with than the unknown.

''It's still distressing and painful and traumatic, but there is an

option to move on,'' he says. ''Often people with this

sort of problem get stuck and the problem becomes their

life.''

Blame can become a problem for those who try to re-write history in

their mind, whether self-blame (''oh, if only I had left

five minutes earlier''), or blame directed at the

child's school or the child's other parent.

Gorovic's approach to trying to help someone in this situation is

to set up some structure for the person hurting and

struggling with no answers.

Practical concerns can be addressed - ''like if it keeps them awake

at night and because they can't sleep, they can't

function. Or maybe they're always in a state of alert:

walking down the street then panicking.''

Gorovic's aim would be to help the parent or affected person get on

with their lives: ''Not to forget about it, not to get

over it, but to be able to find meaning in their own

life once the child is gone. To live their own lives

even though the child is not there.

''One approach I take when somebody has lost a loved one is to say,

'What would this person want from you? Would they want

you to go on crying and put your life on hold? Would

they want you to do something else?' '' |