|

The case of one missing boy cast a shadow over a generation of American

children. Last week brought another sad reminder

|

|

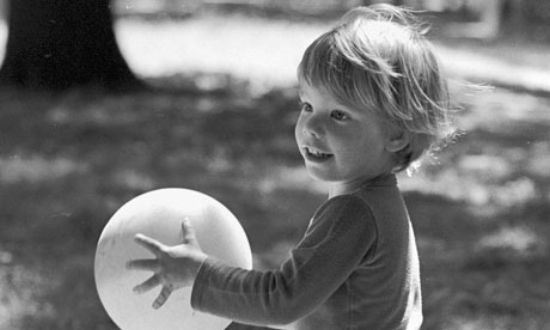

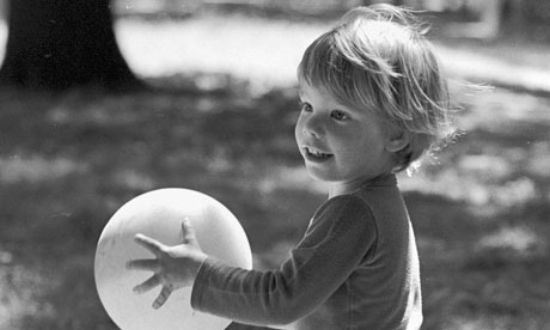

Etan Patz ... his disappearance woke up New

York parents to the dangers of the street. Photograph:

Stanley K Patz/AP |

Last Thursday, the

pickaxes arrived. On Prince Street in the SoHo area of downtown

Manhattan, 40 investigators turned up, armed with equipment to dig up a

basement beneath what is now a jeans store. To New York's shock, sadness

and relief, it was possible that, less than a block from where his

parents lived, Etan Patz had been found.

Almost 30 years before Madeleine McCann disappeared from a hotel bed in

Praia da Luz, a six-year-old boy named Etan Patz (pronounced Ay-tahn

Pay-ts) walked out of his parents' home in SoHo, wearing his beloved

pilot's cap and a corduroy jacket. It was the first time he had been

allowed to go to school on his own and his parents, Stanley and Julie,

had only relented, reluctantly, after much pleading from their son. It

was not until the end of the day that they learned he had never made it

to school. He never even boarded the school bus. On 25 May 1979, Etan

Patz disappeared and his case sparked as much national attention and

ensuing hysteria as Madeleine McCann's would decades later.

The Patz parents have never moved house or changed their phone number,

in the hope that, one day, Etan would find his way home. They watched

from their window last week as the investigators removed concrete and

bricks from the basement of the nearby building which had, according to

the New York Post, been used as a play area for local children when Etan

was little. They had to listen to the noises of investigators searching

for their son's remains while they stayed behind a locked door, still

waiting for Etan.

Although Etan himself disappeared, his shadow was long and dark, and all

children, including me, who grew up in New York in the late 70s and

early 80s lived under it. Stanley Patz was a photographer and pictures

of his son tender, unforgettable and, suddenly, ubiquitous filled

the city. Everyone knew what Etan looked like, but no one would see him

again. Even if your parents protected you from the specifics of Etan's

disappearance, you felt its ramifications, either through your parents

being more vigilant "His vanishing ushered in the modern era of

permanently heightened alert about the dangers of letting children walk

the streets alone," as the New York Times put it or through the new

focus on missing children in general.

Putting photos of missing children on the backs of milk cartons was just

one of the developments to come out of Etan's disappearance another

was the establishment of National Missing Children's Day on 25 May, the

day he vanished and he, of course, was one of the first children to

feature.

As soon as I was old enough to read, I studied the milk carton notices

carefully as I ate my breakfast. I would always check to see whether the

missing child lived in New York, like I did, whether they had a sister,

like I did. The more different they were from me, I'd tell myself, the

safer I was.

I remember learning about Etan very well, over my Cheerios. He was from

New York. He had a sister. He was Jewish, too. He was born six years

before me, but it felt close enough. If the kidnapping of Etan Patz woke

up New York parents to the dangers of the street, it taught me that

mothers and fathers could not always protect their children, children

just like me.

While Stan and Julie Patz have done much to try to prevent other parents

from going through what they have suffered, their pursuit for justice

for their own son has consisted of nothing but more pain and

disappointment. To help him get through the first three years of his

son's disappearance, Stan tried to convince himself that Etan had been

taken by "a deranged but well-intentioned motherly type [who] was loving

Etan somewhere," Lisa R Cohen writes in her 2009 book on the case, After

Etan: The Missing Child Case that Held America Captive. This

self-sustaining myth soon collapsed and he, along with many others,

strongly suspected José Ramos, a drifter who had known one of Etan's

babysitters. Ramos admitted in 1982 he had tried to molest the little

boy the day he disappeared but insisted he hadn't killed him. Ramos has

been in prison since 1987 for other abuses but no one could connect him

to Etan's murder, and there was no body in any case. But every year, on

Etan's birthday and on the anniversary of his disappearance, Stan sends

Ramos a lost child poster of Etan and writes on the back: "What did you

do to my little boy?"

Last week, a police dog showed signs of smelling human remains in the

basement and another suspect, a local handyman who had known Etan,

emerged when he blurted out: "What if the body was moved?" But by

Tuesday, there was disappointment, again. Nothing had been found in the

basement. The investigators went home. Stan and Julie stayed inside.

According to the US Department of Justice, 2,185 children are reported

missing in America every single day. In a fairer world, all would get

the attention that Etan did. In a fair world, none would vanish at all.

For whatever reason, one case occasionally emerges that haunts a

generation. While the other children of their era grow up, become adults

and have children of their own, those lost few are frozen forever in the

photographs their desperate parents release to the media, their toothy

childish smiles the only replies to unanswered questions. |