|

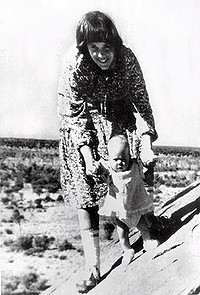

| Lindy

Chamberlain and her daughter, Azaria, shortly before

Azaria's disappearance. |

THE treatment of Lindy Chamberlain was the closest I have come to seeing

a witch being burned alive.

Recently, I read a remark she made when asked about the abducted English

child Madeleine McCann, the treatment of whose parents by the English

tabloids shocked the Leveson inquiry. ''The people want answers,'' she

said, ''and if they haven't got them they'll invent them.''

The most incredible fact in the Chamberlain case is that for 24 hours,

the police, the other people in the camping ground and the Aboriginal

tracker agreed with Lindy Chamberlain in believing that a dingo had

taken her baby Azaria. Then another mind got involved, European in

origin, based in cities and largely divorced from the land.

For a period thereafter, Australia was like a European village in the

Middle Ages. Lindy Chamberlain had a strange religion (she was a

Seventh-day Adventist). A photo showed her baby dressed in black. Who

dresses a baby in black? She didn't show emotion. What sort of mother

doesn't show emotion after her baby is killed?

I still remember the speed with which the rumour that the name Azaria

meant ''sacrifice in the desert'' swept past. It was like an express

train carrying the (false) news to all corners of the land. People said

the mother should be hanged. Instead, after a barrage of ''expert''

witnesses hostile to her, she was sentenced to life imprisonment with

hard labour.

Did the venue matter? You bet. Uluru is an everyday Australian symbol,

but one that has active Aboriginal meanings and powers. In a significant

irony, its whitefella name, Ayers Rock, comes from a whitefella who

never even saw the place. Uluru has a dreaming about a dingo who is

hostile to humans and eats babies. The story is part of the Aboriginal

knowledge of the place.

In the mid-1990s, I was at Kiwirrkurra, a Pintupi community about 500

kilometres north-west of Uluru. Only 10 years earlier, a family had

walked into Kiwirrkurra from the desert, where they had been living a

traditional nomadic lifestyle - this was their first contact with

whites.

At Kiwirrkurra, I met a white woman whose daughter went missing in the

surrounding desert. She had watched, impatient, as an old Pintupi man

spent hours studying a mass of tracks where the child had been playing,

unthreading the footprints one from another like strands of a rope. Then

he headed off into the desert and found the girl.

The Pintupi man told the child's mother a dingo took Azaria Chamberlain.

Then people who know about such things told me that the people at

Mutitjulu - that is, the local mob at Uluru - never doubted that a dingo

took Azaria. A fourth coronial inquiry now being held in Darwin is

expected to arrive at the same conclusion.

Lindy Chamberlain says maybe now people will understand dingoes are

dangerous.

Last week, walking in the bush, I nearly trod on a snake. There's

nothing like a snake to remind us that the land has another nature, a

nature apart from our own.

Lindy Chamberlain is a story of the land like the story of the explorers

Burke and Wills. They headed off with every advantage mid-19th century

technology could bestow. They set off to conquer the Australian interior

and never returned. Burke and Wills have a unique place not only in the

history of Australian exploration but in the Australian psyche. Lindy

Chamberlain has, too.

To quote an old Australian song, she and her baby are like ''ghosts who

can be heard'' as you pass by that big red rock in the centre of our

land. |