Imagine a time before reality TV,

wall-to-wall celebrities, 24/7 news channels, political spin and the

public relations industry

|

|

Celebrity gossip has forced out a lot of hard news in modern

newspapers |

Believe it or not, once upon a time,

newspapers and television news bulletins were full of actual news

involving actual people, much of it generated by reporters on the crime

beat.

The demise of the crime reporter, and

the decline of investigative journalism in general, has coincided almost

perfectly during the past 20 years with the rise of celebrity news.

Tittle-tattle about soap stars,

Premier League footballers, TV chefs and even those who "starred" in

shows like Big Brother now makes up the bulk of tabloid newspaper

content, and it has seeped inevitably into upmarket papers and TV news

and current affairs programmes.

This is a world in which the first

photograph of TV presenter Davina McCall, pregnant, walking down the

street, was sold to a newspaper for ?7,500.

Death of Fleet Street

Other factors have no doubt played a

part - the rise of public relations (PR) and press officers and the

gradual move away from Fleet Street by the national newspapers meant the

culture of journalists getting out of their offices and chatting to

detectives, lawyers, politicians, entrepreneurs and other "sources" over

a drink in a pub has ebbed away.

"Hard news is declining and there has

been a movement towards 'lifestyle journalism', often provided by PRs or

agencies. It is cheap and fairly easy," says Bob Franklin, professor of

journalism studies at Cardiff University.

He says: "I often wonder why we train

our students to cover the courts and council meetings because when they

get jobs they rarely have to do either. Journalists do not get out of

their offices as much as they used to. There is a lot more juggling the

wires [news agencies] and press releases.

|

Newspapers don't want to run lengthy court reports.

We are playing up to an attention deficit disorder

Duncan Campbell The Guardian

|

After all, discussing the latest

celebrity

dress is easier than uncovering

corruption on a local council."

Duncan Campbell, the Guardian's

long-time crime correspondent, who is retiring this year after four

decades in journalism, says: "Nowadays you get much more homogenous news

with all the media chasing the same stories."

"Most newspapers, and the BBC and

others, have websites and they can see from the number of hits a story

gets what is popular.

"You will find a story about [Cristiano]

Ronaldo or Kate Moss will be massively hit, which you will not

necessarily get from an interesting story with nobody famous in it."

Campbell says crime coverage has been

one of the biggest casualties, with newspapers and broadcasters

massively downsizing their teams.

Retreat of the reporters

Old Bailey reporter Dave St George can

vouch for that.

"I started here in 1969 when I was

asked to supply the Telegraph, Mirror and the Standard," he says.

"In those days PA [the Press

Association] had seven people covering the Old Bailey, and the Express,

Mail and the Times all had staffers down here."

PA now has two hard-working but

over-stretched journalists covering the Old Bailey and supplying copy to

the national newspapers, who long ago withdrew their court reporters

back to their offices.

|

The other day there was a fellow jailed for 30 years

for shooting at a policeman. That would have been a

big story a few years ago, but nowadays it doesn't

even merit a mention

The other day there was a fellow jailed for 30 years

for shooting at a policeman. That would have been a

big story a few years ago, but nowadays it doesn't

even merit a mention

|

St George says: "I used to get four or

five stories in the Telegraph every day. Now I never hear from the

newsdesks from one year to the next. They're filling the papers with all

this other stuff.

"The other day there was a fellow

jailed for 30 years for shooting at a policeman. That would have been a

big story a few years ago, but nowadays it doesn't even merit a

mention," St George says.

The case of Carlton Sam only merited

three paragraphs in the Sun and one paragraph in the Mirror. No other

national newspaper reported it.

Ironically the reduction in coverage

coincides with a rise in the number of crimes.

"In the 1970s if we had one homicide a

fortnight it was big news," St George says.

This week there are 11 ongoing murder

trials at the Old Bailey.

So have readers just had their fill of

crime? Would they rather read about the new mansion Ronaldo has bought

or discover why an EastEnders actress has split up with her boyfriend?

Yes, says Mark Frith, former editor of

Heat magazine and author of The Celeb Diaries.

"There was an untapped market and the

whole [Princess] Diana phenomenon showed that people wanted to read

about people in the public eye," he says.

"Posh and Becks was the start of the

celebrity age and since then it has moved on to people like Jade Goody,

who was the most read story on the BBC website two days running."

|

| Carlton

Sam, who shot at police, barely merited a mention

|

Frith says: "Editors have to decide

which stories will engage their readers and they will not mourn for

stories that they have not got room for."

A spokesman for the Daily Telegraph

told the BBC: "Our aim is to provide up-to-date, reliable news and

comment for our readers from a range of voices. We believe we have been

successful in that, including appealing to changing audiences, which is

why we remain the market-leading news provider."

Professor Justin Lewis, head of the

School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies at Cardiff University,

has conducted research on the changing content of newspapers.

He says: "There is no doubt that

celebrity news as a category has grown markedly, especially in

broadcasting.

"There is a perception that that is

what people want but there is not actually that much evidence that it

is. People may say it sells newspapers, but clearly it doesn't because

circulation is still going down."

But he adds: "I don't think there is a

shortage of crime coverage, but it's just a different type. Big

newsworthy crimes still get covered rather than the day-to-day business

of the courts."

TV to blame?

Jeff Edwards, who was the Mirror's

crime correspondent until being made redundant last year, agrees: "I

don't think crime reporting is dead. There is not a huge dropping off in

interest in law enforcement. But there is a dropping off in stories

about ordinary people."

Professor Franklin says there is no

doubt the courts are not covered like they used to be, but he says there

is still a big demand from the public for crime stories, especially

"cause celebres" like the cases of Madeline McCann and Shannon Matthews.

Campbell says: "Newspapers don't want

to run lengthy court reports. We are playing up to an attention deficit

disorder. There is a feeling that people can't take large chunks of

information, whether it's on radio, on television or in newspapers."

|

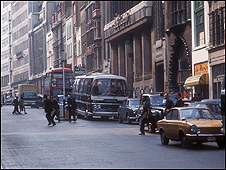

| Fleet

Street has changed out of all recognition since the 1970s |

He pins part of the blame on TV.

"The concept of rolling news, where

the competition is not to explain something better but to have a version

up quicker. Speed, rather than depth, has become the essence," he says.

"Decent court reporting is also very

people-intensive. Sometimes you may have to hang around for a few days

without getting anything in the paper, but you bump into lawyers, police

officers, even defendants and somebody tells you something and you get a

story emerging."

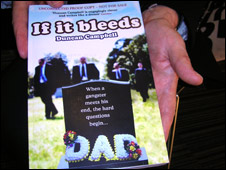

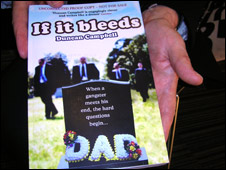

Campbell's latest novel is a "requiem

for the old days of crime reporting" and focuses on an Old Bailey

reporter struggling with a celebrity-obsessed newsdesk.

He sees the same trends in local

newspapers, where cut-backs have meant it is extremely rare to see

journalists at most magistrates' and even crown courts.

But one place where crime reporting

thrives is Scotland, where tabloid papers regularly lead with tales of

organised crime.

The editor of the Sunday Mail, Allan

Rennie, says: "I don't know if it's because Scots like crime stories or

whether organised crime is more visible up here, more like old-fashioned

criminals like the Krays."

Rennie adds: "Nowadays it's a fact of

life that you can't afford to send staff to spend days on end at court."

He thinks one possible answer would be

to allow television cameras inside courts.

Changing media

|

| In

Duncan Campbell's book a court reporter battles with his

newsdesk |

The media has changed enormously since

the 1970s.

Reporters are now equipped with mobile

phones, laptops, Blackberrys and digital cameras and can file copy much

quicker than in the old days.

The general public are often invited

to become "citizen journalists" by e-mailing or texting in photographs

or reportage of incidents they have witnessed, including pictures of

celebs doing embarrassing or even mundane things.

But citizen journalists cannot cover

court cases - they are not trained in the legal pitfalls and are

unlikely to have any shorthand skills - so the criminal justice system

goes under-reported.

Who cares?

But does it matter?

Professor Lewis says: "The danger is

that it potentially distorts our perception of crime."

St George says there is another

danger.

"Princes and paupers and politicians

can get away with murder if there is nobody on the press bench to report

it," he says.

"And if an accused wants to declare

their innocence to the world who is there to report it?"

Campbell says: "Who knows how many

scandals we have missed? People might have got away with a lot of stuff

because there are far less investigative journalists going out and

actually covering things. It's far easier to shove a celebrity picture

on a page rather than go out and find a story."

But he is hopeful for the future.

He says: "There may be a reaction to

the trivialisation of the news, to the spin and the vitriol, in ways I

can't predict. We are in a period of enormous change and people may want

to know about stories in far greater detail."

If It Bleeds, by Duncan

Campbell, is due out this week. |