|

|

| |

|

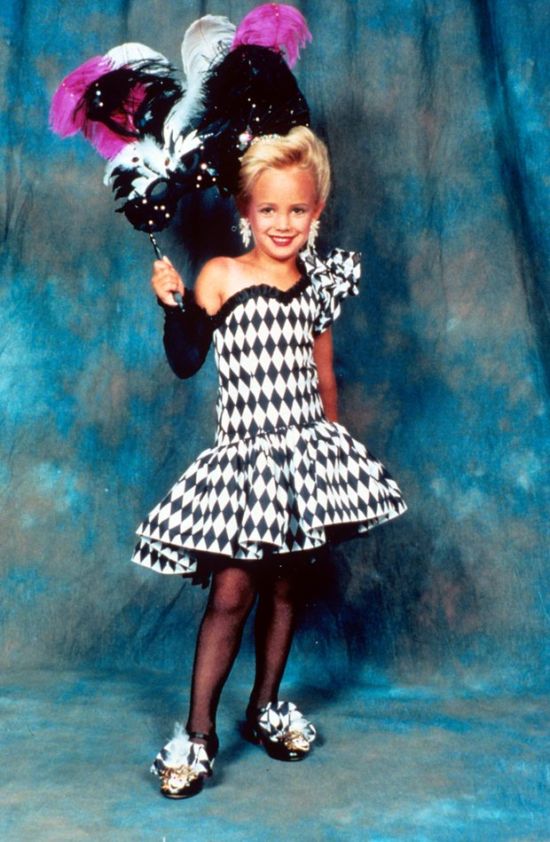

Twenty years on, the unsolved killing of

this six-year-old beauty queen is being

raked over in three new documentaries.

Why did the case inspire such ghoulish

hysteria, while her parents, like those

of Madeleine McCann, were demonised and

placed under suspicion? |

| |

|

|

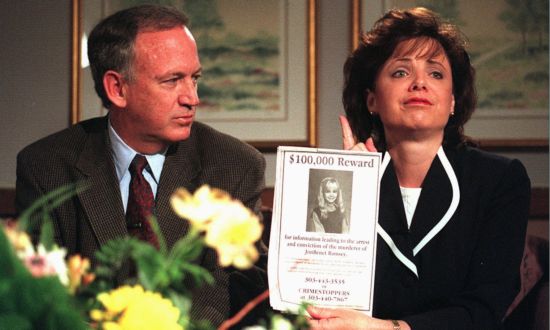

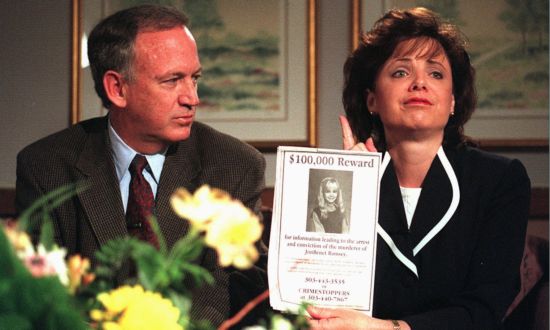

JonBenét’s parents, in 1997,

hold up an advertisement

promising a reward for

information leading to the

arrest and conviction of their

daughter’s killer. Photograph:

Patrick Davison/AP |

| |

|

|

Such

is the level of suspicion in this story

that even the date of death is deemed

proof of a conspiracy. Twenty years ago,

JonBenét Ramsey, a six-year-old girl

known for ever to the world by the

uncomfortably adult poses she struck in

her beauty pageant photos, was found

bludgeoned and garrotted in her family’s

basement in Boulder, Colorado. The

killer has never been found and, ever

since, the case has been picked over by

experts, the tabloids and an endless

slew of internet obsessives.

It is impossible to overstate how huge

this case was – and still is – in the

United States. Every year, the US media

promise “A chilling new discovery” and

“Latest twist”, even though the case

remains as cold as Christmas in

Colorado. There is now not one single

part of this sad tale that has not been

seized on – by the public, by the

police, by JonBenét’s parents, John and

Patsy – as proof of a coverup, even down

to the child’s gravestone near Atlanta,

Georgia, where she was born. There, the

date of death is literally carved in

stone: 25 December 1996. Yet even this

is seen as a lot less stable than its

material suggests. After all, doubters

say, how could John and Patsy have known

that their daughter died on Christmas

Day if they didn’t find her body until

the early afternoon of the 26th? Surely

the gravestone is evidence of their

guilt that so many have long assumed,

despite them being exonerated in 2008 by

DNA evidence?

The few undisputed facts are as follows:

just before 6am on 26 December, Patsy

called the Boulder police department

from her home. Her daughter had been

taken from their home in the middle of

the night, she said. She had found a

two-and-a-half-page ransom note

demanding $118,000 for her safe return.

The police arrived at the Ramsey house,

along with many of the Ramseys’ friends,

who wandered freely around the property.

After the kidnappers failed to call at

the promised time, one of the officers

suggested to John that he look around

the family’s large house. He went down

to the basement with a friend and there

he saw his daughter, bound and gagged.

When he brought her upstairs, it was

obvious she had been dead for some time.

She had been bashed over the head,

strangled with a garrote fashioned out

of a nylon cord and her mother’s

paintbrush, and possibly sexually

assaulted. There was no immediately

obvious sign of a break-in, and the

house was so large, the perpetrator must

have known its layout very well to have

found JonBenét’s bedroom in the middle

of the night and taken her down to the

basement without waking anyone else.

Some historical crime stories fascinate

the public years later because of what

they say about the times in which they

happened. The OJ Simpson case and the

Manson killings are two obvious

examples, both of which have experienced

a revival of interest this year, thanks

to their retelling in pop culture. The

story of JonBenét Ramsey is different.

The case is certainly in the spotlight

again, with three US networks – CBS, A&E

and Investigation Discovery – all

recently screening their takes on the

case to varying degrees of tackiness.

The media coverage of this case was, and

remains, almost unparalleled in its

tawdriness. Photos of the little girl’s

autopsy were bought and published by US

tabloid the Globe. One journalist

claimed to convert from Judaism to

Christianity in order to attend the

Ramsey’s church and glean insights from

staring at the back of John and Patsy’s

heads. (“I had never seen anyone pray

for his own soul the way Patsy was

praying for hers … At that moment, I

decided she was the killer,” the

journalist, Jeff Shapiro, said in

probably the best-known book about the

case, Lawrence Schiller’s Perfect

Murder, Perfect Town.) The whole story

has long been covered in a thick sheen

of schlock. The only interesting thing

about its historical context is that the

case happened in the aftermath of the OJ

Simpson trial, just when the media was

desperately seeking another case that

would similarly hold the public’s

attention.

But while JonBenét’s murder may well

never be solved, there has never been

any mystery about why it still exerts

such a fascination.

Like Madeleine McCann, JonBenét was a

pretty blond child from a well-off

family, allowing the public the pleasure

of looking at this photogenic child

while simultaneously experiencing a

quiet, unacknowledged frisson of

schadenfreude at her parents’ pain.

Add to this the undeniably sexualised

pageant photos, in which the

six-year-old wiggled and pouted in a

manner that looked all the more

fascinatingly horrific after her brutal

death, and you have the perfect

made-for-media confection. But none of

these factors really explains the

passion this case excites, while also

spotlighting how the public demonises

parents involved in stories we fear

could happen to us.

Pretty much from the moment this story

broke, there have been two theories

about what happened: either JonBenét was

killed accidentally by one or both of

her parents, or her then nine-year-old

brother, Burke, and the parents staged a

faked kidnapping to cover up the

killing; or it was a botched kidnapping

by a mystery outsider. Part of the

reason this case has never been solved

is because the Boulder police department

badly bungled the first few days.

Understaffed during Christmas and wholly

unprepared for such an extraordinary

case, they failed to secure the crime

scene. They didn’t even find JonBenét’s

body in the basement, leaving John to do

so hours later. Their relationship with

the Ramseys completely broke down when

they threatened to refuse to release

JonBenét’s body for burial unless the

Ramseys came in for an interview, and

there were frequent leaks from the

Boulder police department to the media.

“The police were not there to help us.

They were there to hang us,” John Ramsey

has said since. A 2015 Reddit ask me

anything (AMA) discussion with former

Boulder police chief Mark Beckner did

little to disprove the Ramseys’ belief

that the police continue to assume they

were guilty. (Beckner has since

expressed regret for the AMA, saying he

hadn’t realised it would be made

public.) |

| |

|

|

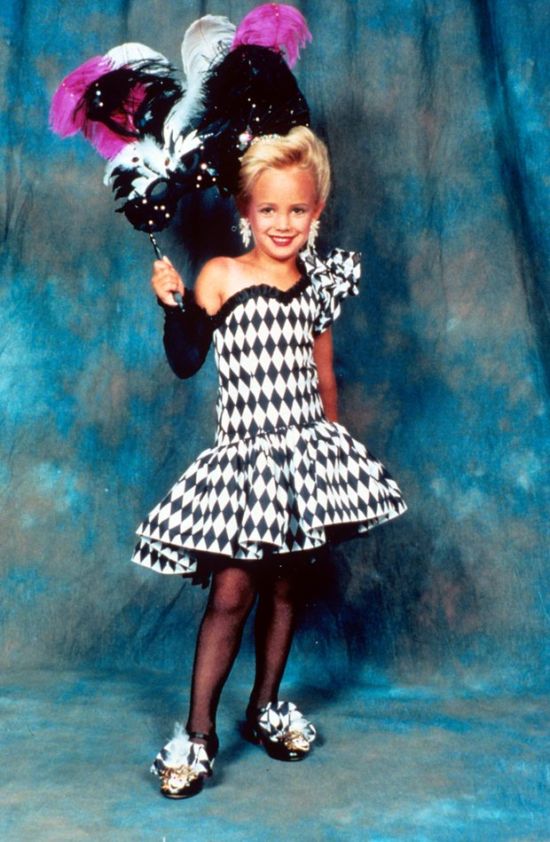

JonBenét Ramsey. This and

other photographs of her

competing in beauty pageants

helped to turn the public

against the family after her

death. Photograph: Sipa

Press/Rex Features |

| |

|

|

“The biggest mistake in this case is

that there was a phenomenal number of

people who decided on the first day that

they knew what happened, and they would

not allow new information to change

that, and that boggles my mind,” says

journalist and Boulderite, Charlie

Brennan, who has been covering the story

from its first days.

However, it is understandable why the

police suspected the Ramseys. When a

child is killed at home, it is

statistically likely that a parental

figure was involved. The Ramseys,

according to the police, were reluctant

to be interviewed (the Ramseys have

vociferously denied this), and John was

overheard on the phone an hour after

finding JonBenét making arrangements for

his family to leave the state (he has

since said he was just trying to keep

them safe). They were also swift to hire

lawyers – suspiciously quick in the eyes

of many. As for the date on her

gravestone, her parents have since said

they chose it because that was the last

time they saw their daughter.

“The Ramsey case is a criminal Rorschach

test – every piece of evidence can be

looked at in several ways, and I’ve

never seen that in any other case,” says

Brennan. One example of this is the

weirdly long ransom letter, demanding a

very specific amount of money, which

happened to be almost exactly what John

Ramsey had received as a bonus that

year. Even weirder, the note was clearly

written in the Ramseys’ house, using a

pad of paper and pen that were there. To

some, this proves the Ramseys must have

written it: what kidnapper would hang

around to write such a long note? But to

others, this is proof that they didn’t.

Why would the Ramseys mention John’s

bonus in the letter? It must have been

someone with knowledge of his

well-publicised business affairs who

wanted to hurt him. The killer could

have broken in while the family was out

on Christmas Day visiting friends, their

defenders say, and written the note

while they were out, lying in wait until

they went to sleep.

Then there are the pageants. Without

question, the images of the little girl

sashaying on stage in makeup, which were

released without her parents’ consent,

helped to turn public opinion against

the Ramsey family. It certainly turned

many people in Boulder against them.

“Boulder sees itself as a very

sophisticated community and a lot of

people figured that this whole spectacle

was beneath them,” says Brennan. “The

Ramseys had only moved to Boulder a few

years earlier [from Georgia], and then

the whole pageant thing came to light,

which was something that was completely

foreign to most people in Colorado and

more associated with the deep south. So

a lot of Boulderites felt: ‘This does

not reflect us, they are not one of

us.’” As a result, Brennan says: “A lot

of people in Boulder feel there is no

mystery – they know who did it.”

Even JonBenét’s parents seemed divided

about the pageant issue. In their book

about the case, The Death of Innocence,

that they wrote together in alternate

sections, John insists beauty pageants

were just “one of her many hobbies”.

Patsy, however, spends the next seven

pages describing her daughter’s “gift”

at “performing” (she also doesn’t

mention any of her daughter’s other

hobbies). Beauty pageants were unusual

in Colorado, she writes, but she had

done them herself when she was younger.

For one, she bought JonBenét “a Ziegfeld

Follies costume, reminiscent of the one

I had worn in the Miss West Virginia

Pageant some 20 years earlier. Like

mother, like daughter.” |

| |

|

|

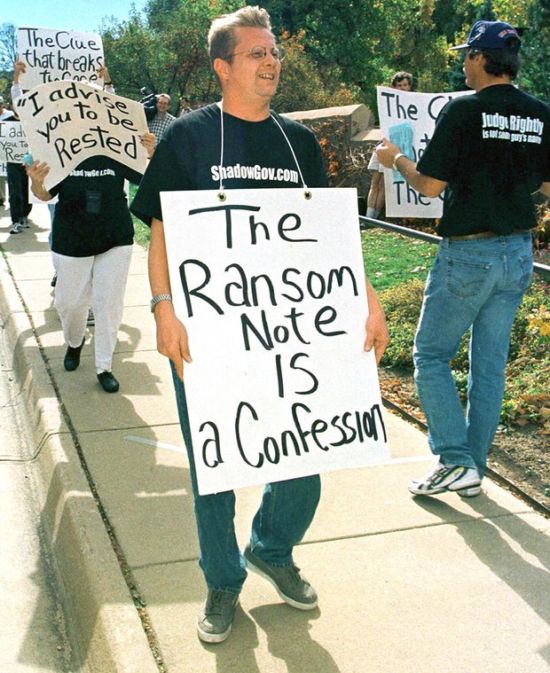

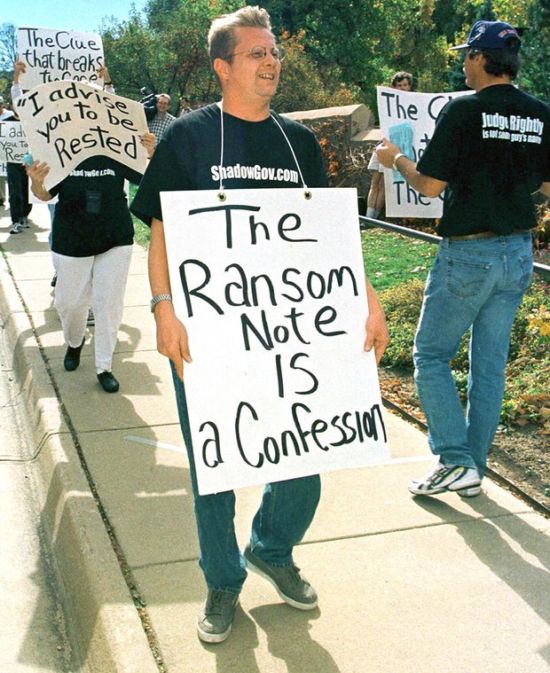

Protesters

unhappy at the lack of a

decision in the murder case

march outside the justice

centre in Boulder, Colorado,

in 1999. Photograph: Reuter |

| |

|

|

So Patsy, in particular, was shocked by

the negative public reaction to the

pageant photos after her daughter’s

murder. One newscaster said the

six-year-old resembled “a hooker”.

Pretty much only pageant photos of

JonBenét were used in the media, even

though she had only been in nine

pageants. There was a definite

intimation in the now-hysterical media

coverage that to put your child in a

beauty pageant was weird, unnatural and

sexually suspect. JonBenét was

simultaneously deified as a photogenic

angel and vilified as a child temptress,

and her parents were criticised for

fetishising her looks, while the public

and media did exactly the same thing

themselves. “What I saw on the pageant

video … you don’t do that to a

six-year-old,” JonBenét’s former dance

teacher, Kit Andrew, says in Perfect

Murder, Perfect Town.

But there is an alternative way of

looking at the pageants. Child beauty

contestants, while unusual in Colorado,

are hardly unknown in the US. Thousands

of pageants still take place every year,

and no one is saying every parent

involved is a potential killer. In fact,

far from incriminating the Ramseys, the

pageant photos could be seen as almost

exonerating them: it could very easily

be argued that the pageants brought

JonBenét to the attention of a local

paedophile, and several have since been

suspected, but never charged.

John and Patsy’s general demeanour was

also deemed suspicious by the police,

the media and the public. “The Ramseys

didn’t appear to behave the way parents

in this situation are ‘supposed’ to

behave. They didn’t cling together and

constantly comfort and reassure each

other,” John Douglas writes in The Cases

That Haunt Us.

But John and Patsy were, they write

themselves, “in shock and medicated so

we could function” for weeks after the

murder. So to judge how they spoke,

looked and interacted as being

indicative of something was not really

fair. But this is what happens to every

parent who loses a child in a

high-profile case: their behaviour is

scrutinised for clues.

When a parent loses a child, the most

natural human response is sympathy. But

that is not what many feel for parents

in high-profile cases.

When Madeleine McCann went missing in

2007, her father, Gerry, and in

particular her mother, Kate, were widely

criticised: Gerry, some sniped, was too

articulate and Kate looked too pretty.

What kind of mother puts on eye shadow

when her daughter is missing?

Kerry Needham was dismissed as a

feckless teenage mother when her baby

son, Ben, went missing on Kos in 1991.

When two-year-old Lane Graves was killed

by an alligator at Disney World in a

freak accident earlier this year,

parenting chat sites were swamped with

people criticising the parents for

letting a little boy play near the water

in the evening, as though that were

unusual on a Florida holiday.

Parent-blaming is all-too-common these

days, and usually the point is to make

other parents feel better about their

own parenting skills. But in cases such

as that of JonBenét, something else is

going on. By demonising parents who have

suffered a terrible trauma, the rest of

us can reassure ourselves that they are

different from us: those parents are

flawed, even evil, and we are good and

therefore our child will never go

missing – in Kos, in Praia de Luz, from

our house in the middle of the night –

like theirs did. The rush to blame

JonBenét’s parents can also be partly

put down to the public needing to

reassure themselves that, contrary to

what the Ramseys said, killers don’t

break into houses and murder children

where they should be most safe. That

only happens when the parents themselves

are killers. And yet.

Brennan says: “In 2000, I wrote a piece

that ran in the Dallas Morning News

pointing out that, nine months after

this crime, someone broke into a house

near the Ramsey house and was in the

process of assaulting a nine-year-old

girl in the middle of the night and was

chased out by her mother. The girl went

to the same dance studio as JonBenét.

The police said they believed it had no

connection to the Ramsey case.”

After writing about the case for 20

years, Brennan says he has come to

believe the family weren’t involved: “If

you look at the autopsy photos and you

see the deep furrow in her neck created

by that ligature, you see a tremendous

amount of force was used. That does not

suggest staging to me – the person who

did it, meant it. But the Ramseys have

nothing in their background to suggest

that this level of evil dwelled in their

hearts,” he says. But this theory, like

the ones about whether the Ramseys

behaved how they were “supposed” to,

relies on imagining how we would behave

if our child had been killed, or if we

had killed them accidentally. But no one

can do that accurately. And anyway, it’s

irrelevant, since the case is about the

Ramseys, not anyone else.

It is entirely possible JonBenét was

killed by a member of her family. It is

also very likely the case will never be

solved: Patsy has since died and the

case gets colder every year. The

ghoulish hysteria around her murder has

lasted more than three times longer than

JonBenét’s life did. “I’ve covered lots

of big stories: the Challenger,

presidential elections. But this – it is

something that I’m thinking about all

the time,” says Brennan. “It is an

impossibly complex, seemingly unsolvable

riddle.” It is also the death of a

child, killed with shocking brutality.

But it’s hard to see the truth beneath

the schlock.

The Killing of JonBenét: Her Father

Speaks, 9pm, 11 December, Crime and

Investigation; Who Killed JonBenét?

Lifetime Movie, 10pm, 18 December; The

Case of JonBenét Ramsey, 22 December,

More4 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|